THE PLACES WE visited when we were young stand stubbornly, often joyously, in our minds and hearts.

In this collection, we delve into these memories as illuminated by long-ago travel photos — many of them submitted by readers of our “Now & Then” column.

We also return to these sites, in images kindly contributed by professional and amateur photographers in places that we collectively cannot or choose not to revisit at present because of the coronavirus.

It’s a way of taking vacations without leaving home. Enjoy the trip!

New York Harbor, 1963

“I was obviously very secure in myself … that innocent confidence.”

— Marti Dell

It is her first memory.

Climbing the Statue of Liberty steps at age 3½ in June 1963, the girl from Green Lake could see only her mother’s pregnant belly and the knees of others.

“I very clearly remember my father picking me up and leaning me over the railing so I could look down on the heads of everybody else on the spiral staircase,” she says.

New York Harbor was a vivid stop on a six-week family tour of the Northeast. Her parents, University of Washington graduates Michael and Beverly Dell, were headed that fall to the University of Michigan for master’s work.

Marti doesn’t recall ferrying to the Statue of Liberty. In fact, she first saw the photo of her in red duds on the deck a few years ago. It was among 15 to 20 slides her father had tucked away.

“I saw that, and all I thought was, ‘Oh my gosh; I’m stylin’.’ I have the whole model’s pout and everything,” she says. “I don’t know where that came from, but I was obviously very secure in myself at that point — the whole matching red shoes and belt and sweater, not having a care in the world.”

She revisited the statue six years ago to research her great-grandparents, Russian Germans who had immigrated via nearby Ellis Island.

A Portland attorney, Marti looks wistfully at the 1963 photo: “There’s some of me that wishes I still had that sort of innocent security. As you get older, you have self-security in other ways, but not quite that innocent confidence.”

Mount Rushmore, 1994

“When I was young, I would hear about a place … and wanted to see it.”

— Hai Thi Nguyen

When legendary climber George Mallory was asked why he wanted to scale Everest, he uttered what are now perhaps the three most famous words in mountaineering: “Because it’s there.”

Hai Thi Nguyen has a similarly motivating reason for her travel passion. “Curiosity,” she declares. “When I was young, I would hear about a place — Old Faithful, the Eiffel Tower, Vatican City — and wanted to see it.”

But her envisioned trips were delayed by decades of conflict, exodus and building a new life.

After the Vietnam War, Hai Thi and her husband, Khanh Tran, joined hundreds of thousands of other refugees, finally arriving in the United States with an infant son in 1982.

In Vietnam, Hai Thi had taught biology at a high school. In Seattle, she trained to be a nurse, while Khanh, formerly a civil engineer, found contracting work. Two more children arrived.

Hai Thi began to realize her travel dreams in 1992.

In a thick family album, along photos of a sunny Oregon coast, her all-caps annotation reads: “First ‘real’ vacation since coming to the U.S.A.” For two weeks in June, the family circled the West, exploring California, Arizona, Wyoming, Utah and Montana. In 1994, they visited Mount Rushmore in South Dakota.

Each subsequent year, the travel gyre widened exponentially, at first encompassing the Americas, then Europe, Asia, North Africa, Russia and Australia. This past summer, Hai Thi, widowed and in her mid-60s, spent two months on a solo road trip to Maine. Why? With a shrug, she states the constant reason: “Because I’d never seen it before.”

Copenhagen, 1965

“A test of independence … I passed reasonably well.”

— Astrid Anderson Bear

Just 10, Astrid Anderson was a stranger in a strange land.

Flying on her own from San Francisco to Copenhagen, with a refueling in Iceland, she watched other passengers deboard the plane. The flight attendant assigned to escort her was nowhere to be found. So Astrid pulled down her small carry-on bag and headed for the exit.

In June 1965, Copenhagen’s international airport was one of Europe’s busiest and largest, so Astrid was relieved to pass through Customs and Immigration and meet, for the first time, the Danish relatives with whom she would spend the summer.

Her father, science-fiction author Poul Anderson, would attend Loncon II, an international sci-fi convention in London, in late August. So he and his wife, Karen, after sending Astrid to Denmark, enjoyed their own vacation, starting with a slow boat to Greece.

Astrid’s experience was formative: “It was a transitional time, a test of independence, which I think I passed reasonably well.”

Denmark’s long history impressed her. “In Copenhagen, you walk streets that have been there for more than 500 years. In the States, you’re hard-pressed to find anything more than 100 years old.”

Now Astrid Bear (since marrying science-fiction writer Greg Bear in 1983), she paid regular visits, prepandemic, to Copenhagen and her extended Danish family.

She has found the city largely unchanged. The 17th-century Round Tower, the oldest functioning observatory in Europe, still offers unobstructed harbor views.

“The only additions are the offshore wind turbines, part of a green network that fulfills nearly half of Denmark’s electrical needs.”

Iguazú Falls, Argentina, 2011

“It was a moment of grace and gratitude.”

— Lizeth Gutierrez

Nothing has quite filled the senses of 31-year-old Lizeth Gutierrez as being drenched by legendary Iguazú Falls on the border of Argentina and Brazil.

“The waterfalls go for miles, and you feel the breeze, the intensity of the water and the green of the forest,” she says. “There’s just an electrifying energy.”

The feeling also was deeply meaningful. “It made me feel more appreciative,” says the American studies professor and middle-school administrator from Kenmore, who grew up in East L.A.

Lizeth’s excursion to Iguazú Falls came 10 years ago, while she was a student at Grinnell College in Iowa. From Grinnell, she joined a five-month study-abroad program based in Buenos Aires. There, she and friends booked several vacations, including to the falls.

“To be in this place with an abundance of beauty was breathtaking,” she says. “I felt, ‘Wow; this is accessible to me, too, an inner-city girl.’ It was a moment of grace and gratitude.”

She would love to return with her daughter, Isabella, 2, and retrace her steps. “Those trips introduced me to a whole different world, and I was able to dream bigger because of that. I want my daughter to know that she can dream big, that the world is hers. Oftentimes such trips allow us to get outside of our bubble, and I would love for her to experience some of that magic for herself.”

The JFK Eternal Flame at Arlington National Cemetery, 1966

“There was absolute devastation.”

— Linda Turner

She was a 6-year-old tag-along from West Seattle to provide company for a Tri-Cities cousin seven months older. The cousin’s parents were leading a cross-country summer 1966 car trip during which the two kids sometimes had turf fights in the Cadillac’s broad back seat.

“It was a love-hate relationship the whole time,” says Linda Turner. “Sometimes I would be literally sitting on the floor behind the passenger seat with my back against the door and my nose in a book.”

But when they got to Arlington National Cemetery and the eternal flame marking the grave of assassinated President John F. Kennedy, the girls knew something was up.

“I’m sure they gave us instructions on ‘You need to be quiet’ and ‘Behave’ and ‘We’re going to do this’ and why we were doing it. … There was absolute devastation. It was heart-rending to the family around me and to people who were much more aware of the history at the time.”

Linda says it was “obvious that my aunt took a lot of care in making sure that we were dressed nicely.” Their hair was bound in tidy ponytails. “That was a challenge, because neither of us particularly cared to have our hair done.”

What impresses Linda today was the site’s austerity. “For such a large public figure and important monument, they had a small, white picket fence, and you are not more than a few feet from the gravesite. That is totally amazing.”

She has never returned. But doing so “is certainly on the table.”

Expo ’74, Spokane, 1974

“This must have been like what Century 21 was like.”

— Gavin MacDougall

The 9-year-old Queen Anne boy was jazzed. Gavin and his parents, Bob MacDougall and Barbara Zerbach, once again were headed cross-state to his mom’s hometown, Spokane.

But this time it was to see a world’s fair, and he could record it all on his grandmother’s primitive Kodak Instamatic X-15.

“I was excited I was going to have a camera,” Gavin says. “It was a big deal. When I look back on these pictures, I can see the germ of my eye developing, how I consciously composed things a little off-center. It was natural, trial and error.”

His photographic enjoyment was so intense, he was even “taking pictures of pictures being taken.”

The image of Gavin aiming his lens while on the Sky Ride with his dad was taken by his grounded mom. It’s easy to imagine the smile on Gavin’s face.

His overall joy derived from the “sensory overload” of the spectacle. “I had a clue, because I knew where the Seattle Center came from,” he says. “I looked at it as, ‘This must have been like what Century 21 was like.’ It was not that old, but it predated me.”

On the Sky Ride, he even passed two clowns. “They were off-duty,” he says, “but as soon as they realized my camera was aimed at them, they clicked back into character.”

Gavin has worked as an office manager and bookkeeper, but his heart lies in archival work. He keenly senses its value. “After a while,” he says, “your memories are the pictures, and everything else fades.”

Chicago lakeshore, 1988

“To explore without having to go on an expedition.”

— Elancia (Lancie) Williamson

Growing up with four siblings on the west side of Chicago, Elancia (Lancie) Williamson remembers childhood as a routine of activities at home and school. But a few special times each year, her parents took the troupe on a one-day journey to the wonderland of Chicago’s lakeshore.

“It was like taking a vacation,” says Lancie. “It was being able to explore without having to go on an expedition.”

In a weathered print from 1988, the 5-year-old wears a colorful sun dress while posing with her sisters during a badminton match. Off-camera, their mom holds their baby brother, and their dad captures the image.

She recalls the Windy City breezes streaming through her hair. “We would always lose our barrettes,” she says. “You’d get in trouble if you did that, so you couldn’t play around too much, and made sure that you kept yourself together.”

Besides the lakeshore, beckoning were a nearby nature museum and Lincoln Park Zoo. “Every time we had to go home,” she says, “some of us were crying. We really wanted to stay out there.”

Today a Belltown resident and an elementary library paraeducator in Auburn, Lancie attributes her adventuresome curiosity to those precious early family outings. “It still feels like a little bit of a vacation, because I can daydream and imagine a world where I can do that every day.”

Australian Outback, 1986

“I was pinching myself, thinking: ‘Wow; this is epic!’ ”

— Bruce Greeley

Bruce Greeley, now a King County librarian, had joined the Merchant Marine in his early 20s, lured from Seattle by the ocean’s call.

“It was the perfect young person’s gig,” he says. “I had no possessions, no roots, nothing tying me down.” Shipboard jobs might last half a year, followed by months of leave.

Unlike most of his shipmates, Bruce spent free time traveling the world. In 1982, at an exhibit at London’s Marlborough House, he saw a photo that redirected his life.

It portrayed the “mud men” of Papua, New Guinea’s, Asaro tribe and their clay masks. “All I could think was: ‘I’ve got to go there.’ ”

After working on American “love boats” cruising the Hawaiian Islands, Bruce in 1986 launched on a grander expedition. First came many stops: Fiji; the Cook Islands; New Zealand; then Australia, where his vacation photo was snapped.

For days, he’d hitchhiked across the country in 100-degree heat, bound for Uluru/Ayers Rock, a red sandstone mountain sacred to Australia’s Aborigines.

“I was pinching myself, thinking: ‘Wow; this is epic!’ ” he says. “But like all of life’s events, you see it, and it’s gone, and you have to move on.”

His journey wasn’t over. He visited Papua’s “mud men” and met his future wife, Karen. While crossing southeast Asia, he learned he was accepted at the University of Washington to finish his undergraduate degree. Almost 30, he headed home to sink some roots.

Lake Michigan chalet, 1966

“It was magical … The soul is still there.”

— Kristen Woodward

Arms outstretched as a young girl, she had a nonverbal part in a makeshift production. Kristen Lidke was portraying “the horizon.”

The play was “Let the Pages Go Walking through the Yellow Fingers,” spoofing a phone company Yellow Pages ad slogan: “Let Your Fingers Do the Walking.” The setting was a tiny stage inside an A-frame chalet, part of a Western Michigan lakeside resort whose origins stretch to 1894 and whose name — Mich-Ill-Inda (later Michillinda) — stems from the investors’ home states: Michigan, Illinois and Indiana.

It was the destination for yearly trips taken by two Michigan families in the late 1960s and early ’70s. The memories of the three tykes who shared the summer sojourns are a sensory extravaganza: walks and sunsets, bonfires and singalongs, wild raspberries and fragrant pine trees.

“It was magical,” says Kristen (now Woodward) of Seattle’s Westlake neighborhood, who grew up in Ann Arbor. Readily agreeing are her cousins, siblings Renee DePlanche Snyder and Brad DePlanche, who were raised in the nearby Michigan town of Plymouth and as adults settled separately 30 miles away in Brighton.

Their childhood Michillinda recollections tumble out: a father winning a “best legs” contest. A first dive into a swimming pool. The ring of a dinner bell. The tree-lined driveway to the massive lodge.

The lodge burned down in 2012, but the chalet, built in 1965, remains standing to unite the trio in warm chats and yearnings to return.

“It holds such memories whether the lodge is there or not,” Kristen says. “You can still feel everything. The soul is still there.”

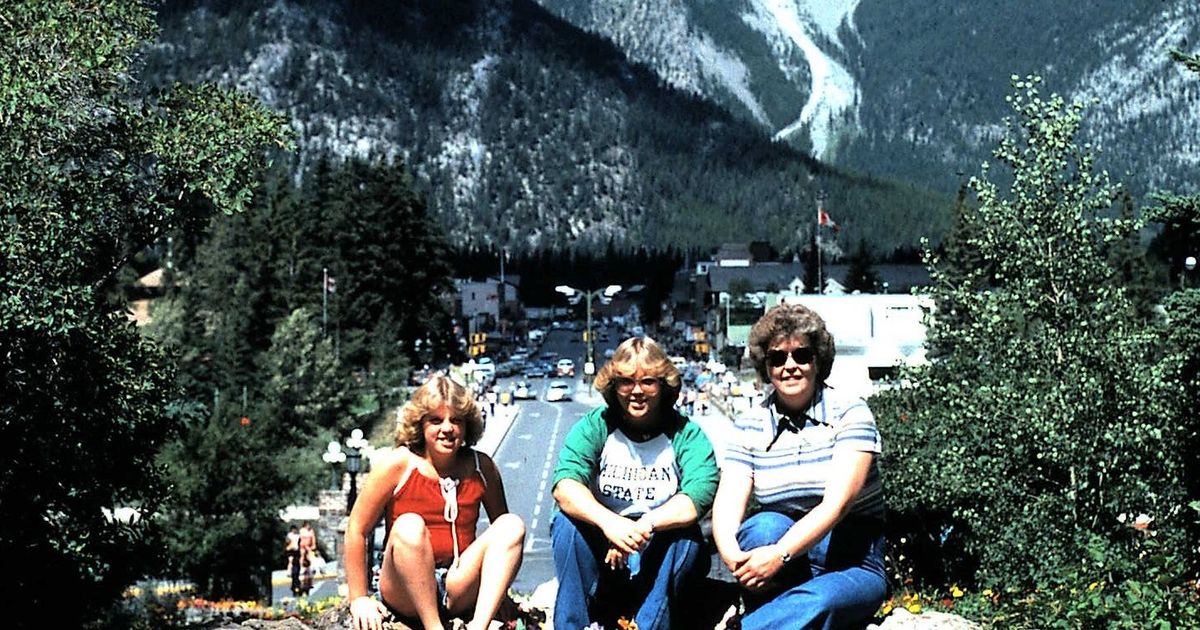

Banff, Alberta, 1979

“I had never seen a lake that was so blissfully blue.”

— Kara Kyro

A high-school principal in Oak Park, Michigan, Richard Kyro made the most of the calendar.

“We went on vacation every summer,” recalls daughter Kara, now a Boeing software engineer. “We drove across the country in the family motor home for a minimum of four weeks.”

Of all their destinations, Banff, Alberta, was Kara’s favorite. She pronounced it “the most beautiful place on Earth.”

Nestled high in the Canadian Rockies, Banff was first settled in the 1880s after the arrival of the transcontinental railway through Bow Valley.

In 1883, three Canadian Pacific Railway workers happened upon a cluster of natural hot springs. Their competing claims seeking to develop the area inspired the Canadian government in 1885 to establish a protective reserve. It became Canada’s first national park.

At 11, Kara was stunned by glacial-fed Lake Louise. “We were flatlanders from Michigan. I had never seen a lake that was so blissfully blue and have always remembered learning about glacier silt that absorbs and scatters sunlight across that spectrum.”

The photo taken by her father from Banff’s Cascade Garden overlooks Banff Avenue, with Cascade Mountain towering over the town. The garden also is home to the Tudor Revival-style Banff National Park Administration Building.

To mark her 50th birthday in 2018, Kara revisited her favorite Banff locations. “It was the best trip ever,” she says. Her affinity for the landscape led her to move to Seattle.

“I’ve been here almost 20 years now and so love the mountains and the water. I can’t imagine not being near them.”

Pinoy Hill, Seward Park, 1954

“You really want to hold on to your culture.”

— Ranesto (Ron) Angeles

When you’re only 4, a car trip can feel like a vacation.

So it was for Ranesto (Ron) Angeles in 1954, when his parents packed him and a sister into their Studebaker and drove from their High Point home in West Seattle to an annual festival on July 4, attended by some 150 Filipinos, at an upper Seward Park meadow known as Pinoy (Filipino) Hill.

“It was very exciting,” he says. “You basically had the park to yourself. You could go swimming in the lake. I remember blowing off a few firecrackers over in the woods. We had sack races and egg-throws.”

But he soon learned it also was a cultural celebration, feting the Philippines’ 1946 independence. “We had traditional foods, like pancit and adobo,” he says. “Most Filipinos lived in the Central Area or Rainier Valley, so to travel all the way over to Seward Park was an opportunity to see the rest of our community.”

His parents danced with the Philippine War Brides Association. Later, during Seafair’s annual Pista sa Nayon (town festival), his children did Filipino folk-dancing.

“It’s really important, because you don’t learn these things in school,” says Ron, retired after a three-decade career as a city liaison. “These are things that if you’re not learning them at home, you’re just not learning it. Many in my generation have assimilated so much into American culture that we don’t speak a dialect. But nowadays, for many Filipinos, you really want to hold onto your culture. It’s important for our generation to pass that along to other generations.”

Paris, 1967

A highlight of their lives.

— The Rev. Theodore and Cherry Dorpat

As World War I ended in 1918, the Rev. Theodore “Ted” Dorpat was ordained by the Lutheran church. His pastorates traversed Minnesota, Montana and North Dakota before he settled in Spokane, where he was renowned for inspiring sermons, a plummy voice and palpable charisma.

A grateful congregation marked his 50th ecclesiastical year with a generous gift. For Pastor Ted and his wife, Cherry, they funded a European vacation.

The pastor’s son Paul Dorpat, historian and founder of our “Now & Then” column, allows that the 1967 trip was their only venture abroad and certainly a highlight of their lives.

“My dad was fluent in German,” notes Paul, whose basso profundo tones echo his father’s, “so I’d expect that their tour extended to a few German-speaking countries as well.”

Examining the photo of the reverend and his wife, gazing fondly at each other with the Eiffel Tower behind them, members of the Dorpat clan note Cherry is wearing her Sunday best with her usual pink hat.

No recordings exist of Pastor Ted, who died in the mid-1980s. But Jack Arkills, a member of his congregation and a boyhood friend of Paul’s, believes that he later heard the reverend’s reverberant tones. During lifesaving surgery following a work accident, Jack describes a near-death experience: “I was in a dark tunnel heading toward a bright light. Before I could go on, a familiar voice told me to turn back, that it wasn’t my time. It sounded just like Pastor Dorpat.”

More Stories

Cruises from Fremantle: A Gateway to Memorable Journeys

Camping Axes: The Essential Tool for Outdoor Adventures

Why Poland Should Be Your Next Winter Destination: A Guide to Unforgettable Winter Escapes